No, President Bush is no longer in office making decisions. But Obama and Democratic leaders are forced to make many of their decisions based on what they inherited from Bush. Eight years is a long time, and the consequences of Bush’s actions didn’t disappear just because he went back to Texas. Ron Brownstein of the National Journal recently noted what the country is still dealing with, according to recent Census figures, after Bush’s two terms:

On every major measurement, the Census Bureau report shows that the country lost ground during Bush’s two terms. While Bush was in office, the median household income declined, poverty increased, childhood poverty increased even more, and the number of Americans without health insurance spiked. By contrast, the country’s condition improved on each of those measures during Bill Clinton’s two terms, often substantially.

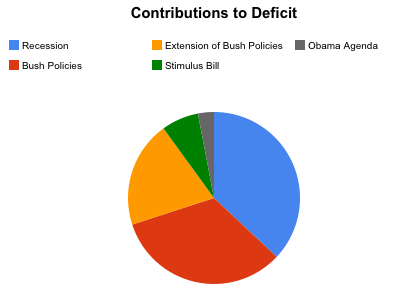

In terms of the deficit that conservatives are always so upset about, Matt Yglesias has put together a pie chart looking at what has actually caused the growth:

So while Fox News pundits complain about the current administration and Congress having to spend so much money, they need to keep in perspective why that spending is necessary.

The Bush legacy of deregulation and what Obama can do

By Reece Rushing, Rick Melberth, Matt Madia | January 22, 2009

Indeed, the Bush administration’s final flurry was just part of an eight-year campaign to gut public safeguards in service to corporate special interests and right-wing ideology. As a result of these actions, the nation’s air and water are less healthy, consumers and investors are more likely to be defrauded, food and other products are less safe, workers are at greater risk of being injured or killed, and public land is being degraded by rampant mining and drilling.

The Bush administration rushed out a host of problematic regulations in its final months. Many of these “midnight” regulations actually represent deregulatory actions that weaken or eliminate safeguards protecting health, safety, the environment, and the public’s general welfare.

The appendix provides a list of several dozen of these regulations. They include, for example:

* A rule that relaxes enforcement against factory-farm runoff

* A rule that permits more waste from mountaintop mining to be dumped into waterways

* A rule designed to protect pharmaceutical companies from being held liable for marketing products they know are unsafe

* A rule that makes it more difficult for workers to take advantage of the Family and Medical Leave Act

* A rule that reduces access of Medicaid beneficiaries to services such as dental and vision care

* A rule that could limit women’s access to reproductive health services.

The Obama administration and new Congress are now faced with the question of how to respond to the Bush administration’s midnight regulation. The response is clear for proposed rules-rules that are in the pipeline but not yet finalized. Executive branch agencies, acting under the direction of new political leadership, can simply stop working on those rules and withdraw them from their regulatory agendas. Or agencies may choose to improve or strengthen Bush-proposed rules before publishing them as final rules.

Final rules present a more difficult problem. Executive branch agencies cannot throw out a final Bush rule with a stroke of a pen. They must conduct an entirely new rulemaking-the legal process by which regulations are made-which often consumes significant time and resources. Unless a rule’s effective date is suspended, which may be possible for a limited number of Bush rules, the rule remains law until a new rulemaking is completed.

Congress also can intervene to block or undo midnight regulation. The Congressional Review Act allows Congress to vote down Bush regulations completed after May 15, 2008, using special expedited procedures. Funding also may be withheld to block implementation or enforcement of undesirable rules.

The last option for dealing with midnight regulation is the courts. Lawsuits are likely to challenge many of the Bush administration’s midnight regulations. The Obama administration will have to decide how to respond to these suits. In some cases, the administration may be able to enter into settlements that effectively torpedo Bush rules.

The Obama administration also must contend with Bush administration rules completed before the “midnight” period. Indeed, the Bush administration’s final flurry was just part of an eight-year campaign to gut public safeguards in service to corporate special interests and right-wing ideology. As a result of these actions, the nation’s air and water are less healthy, consumers and investors are more likely to be defrauded, food and other products are less safe, workers are at greater risk of being injured or killed, and public land is being degraded by rampant mining and drilling. President Obama faces an enormous challenge in reversing the damage.

This task is even more difficult because of procedural roadblocks erected under President Bush that serve to prevent protective regulation. These roadblocks generally skew analytical requirements to favor corporate interests and add bureaucratic layers to gum up the rulemaking process.

As the Obama administration reverses Bush policies, it also must move forward with a positive regulatory agenda that recognizes a fundamental responsibility to protect the public’s health, safety, and general welfare. This will require open and honest assessment of risks, vigorous monitoring and enforcement, and new regulatory protections where there are gaps or where existing protections are not strong enough. The last eight years have left much work to be done.

EXAMPLE:

USDA Blocks Voluntary Mad Cow Testing

The Bush administration has employed an antiquated law in order to stop Creekstone Farms, a natural beef company, from testing its herd for mad cow disease. Creekstone had hoped to voluntarily test its entire herd to reassure customers around the world that its natural beef is safe from the disease, which is more common at industrial factory farms. But the Bush USDA has blocked Creekstone’s access to test kits that can identify the disease markers in processed beef products.At least three cases of mad cow disease have been confirmed in the U.S. since 2003. The Bush administration claims that voluntary testing by proactive beef companies would create confusion and possibly result in a false positive that could scare consumers away from U.S. beef.

The USDA tests less than 1 percent of the nation’s beef cattle for mad cow disease, while many other countries test a far greater percentage of their herds. Creekstone formerly sold its products in Japan but has been blocked from doing so because Japan requires 100 percent testing of its beef for mad cow disease. Creekstone is suing USDA to gain access to the test kits, alleging interference by the Bush administration.

Posted May 9, 2008

EPA Official Ousted for trying to clean up 50 miles of toxic dioxin river polution

At the request of Dow Chemical, the Bush administration forced out one of its own hand-picked EPA regulators on May 1st because she naively attempted to do her job by enforcing the law against Dow. EPA officials told Mary Gade, the federal agency’s top Midwest regulator to step down from her post or be fired by June 1. Bush appointed Gade in 2006, but Gade ran afoul of the White House when she pressured Dow Chemical to clean up dioxin pollution extending 50 miles downstream from the company’s Michigan headquarters. Dow asked EPA headquarters to intervene. In response EPA chief Stephen Johnson’s top deputies repeatedly grilled Gade about the case. When she refused to lay off Dow, they stripped her of her authority and told her to quit or be fired. “There is no question this is about Dow,” Gade said. “I stand behind what I did and what my staff did. I’m proud of what we did.”

Gade was formerly a loyal George W. Bush supporter and adviser. In 2000, she praised then-governor and candidate Bush for his “fresh approach” and “strong leadership.” But her loyalty couldn’t shield her from an administration bent on insulating its chemical industry cronies from public health laws.